The Terminal Warehouse, located at 1011 Jones Street, was an eight-story brick structure occupying the eastern two of three interconnected warehouses. The far east wall bordered the 10th Street viaduct. It was owned by John Nicholas Brown II of Providence, Rhode Island, with management handled by the United States Trust Company. Tenants included M.J.B. Coffee, J.B. Sales, Omaha Western Sales, Omaha Tractor & Equipment, Myers Brokerage, Farmers Union State Exchange, and Rowe Manufacturing.

On Thursday, March 19, 1931, weather was clear, 51°F, with light north wind. At approximately 3:50 p.m., elevator operator Fred Tonack and employee Charles Hines were on the seventh floor, which stored about 400 tons of bagged molasses-beet pulp stacked to the walls. A dull explosion occurred, and smoke issued from a south window. Tonack turned in the alarm at 3:55 p.m.

The warehouse lacked sprinklers or standpipes. Omaha Fire Department companies ascended the north fire escape and interior stairwell. Engine Companies 1 and 12 advanced hose from the fire escape into the seventh floor. Crews encountered dense, sweet-smelling smoke, minimal heat, and no visible flame. The greatest smoke concentration was in the southeast corner, obstructed by stored sacks. Water streams and tools failed to reach the smoldering fire. Ruptured sacks spilled pulp onto the floor, creating slippery slurry.

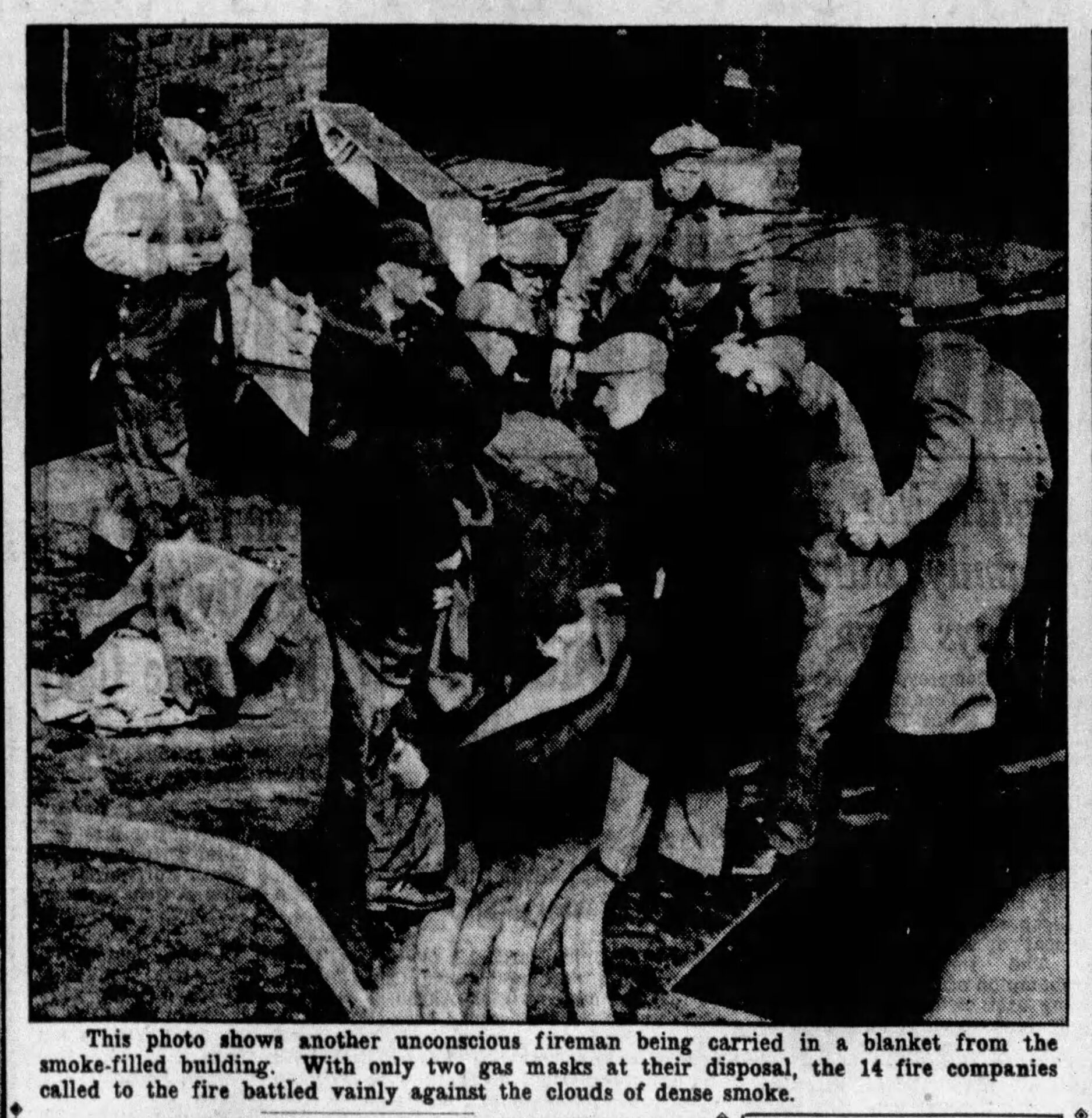

Firefighters began collapsing from the smoke. Water pressure was temporarily cut to switch pumpers, leaving interior crews without charged hose. Assistant Chief Theodore Bernhardt ascended to investigate; more officers, including Fire Chief Patrick Cogan and Assistant Chiefs Patrick Dempsey and Patrick McElligott, were overcome. Within about 20 minutes, the initial attack force — including four chiefs — was incapacitated.

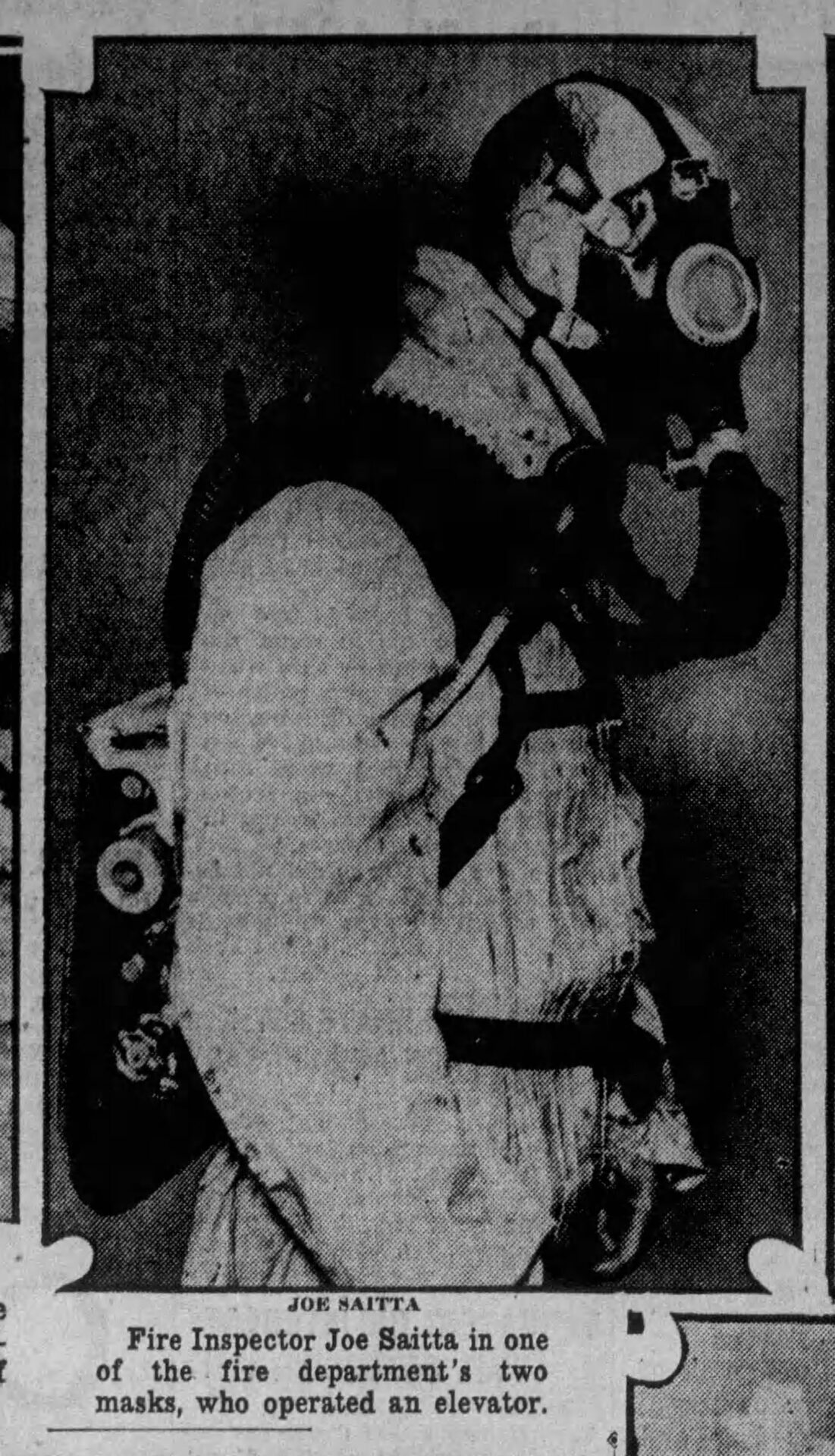

A third alarm was transmitted, bringing all Omaha companies. Master Mechanic Art Olsen and Drillmaster Joe Saitta assumed control. Saitta, the only member trained on new oxygen-breathing apparatus, donned one of two available masks and used the elevator to remove downed firefighters, then broke windows to ventilate.

Rescue operations involved Pacific Storage secretary Evelyn Backstrom, who coordinated calls for ambulances, oxygen, and inhalator teams from Brailey & Dorrance Mortuary, Nebraska Power Company, and Metropolitan Utilities District. Doctors on scene reported the smoke contained no poisons but caused respiratory paralysis.

Once ventilation was established, Battalion Chief Dan O’Connor directed water streams from a ladder on the 10th Street viaduct into the seventh floor. The smoldering fire was extinguished by 7:15 p.m. Overhaul continued until 11:00 p.m.

The fire caused $115,000 in damage ($2.23M in 2023), mostly to stored goods: $60,000 in sugar, $30,000 in farm implements, $8,000 in beet pulp, plus paper and walnuts. Structural damage was about $15,000. The adjacent Pacific Storage building was unharmed.

A total of 27 firefighters were injured; 18 were hospitalized at St. Catherine’s and Lord Lister Hospitals. Most were released within days. Fireman Harry Walsh was initially believed dead but was found breathing at the mortuary and revived. No fatalities occurred.

Laboratory tests by Omaha Testing Laboratories found beet pulp combustion produced about 10% carbon monoxide, 60% carbon dioxide and acid gases, and only 3% oxygen — conditions sufficient to rapidly cause unconsciousness. Investigators speculated spontaneous combustion as the likely cause.

The incident prompted urgent calls for oxygen-breathing apparatus. The department ordered interim masks pending delivery of eight more units. Media criticized prior resistance to purchasing them.

Two days later, the Terminal Warehouse advertised that the fire had been confined to a small area, and business was ongoing.

In October 1933, firefighter Charles T. Fleming, who had been “gassed” at the fire, suffered a mental breakdown linked to cumulative traumatic exposures and retired on disability — considered the fire’s final casualty.

The Terminal Warehouse fire incapacitated much of Omaha’s fire leadership within minutes, yet through coordinated rescues and civilian assistance, no lives were lost. It underscored the hazards of oxygen-deficient atmospheres, the necessity of breathing apparatus, and the importance of incident command under extreme conditions.

Comments